Article from New York Time by Evan Eisenberg "MUSIC; Zen and The Art Of Opera"

NYT Article

I KNEEL on the tatami mat before the Master. For a week I have been banging my head against the koan that is Walter Nowick.

I stare blankly at the Master: I have no answer.

Any moment now he will ring his bell, signifying that our meeting is over: the paper must be put to bed. I will be dismissed, cast back into the world to bang my head some more, no longer paid by the word.

Begin with the bare facts -- a few quick, bold lines, as in an ink painting by Sesshu.

Walter Nowick, 75, is a Juilliard-trained pianist who went to Kyoto, Japan, in 1950, sat in a Zen monastery for 16 years and became a Zen master. After his own master died, he started a Zen community in the woods of Maine, an arrow's flight from the sea.

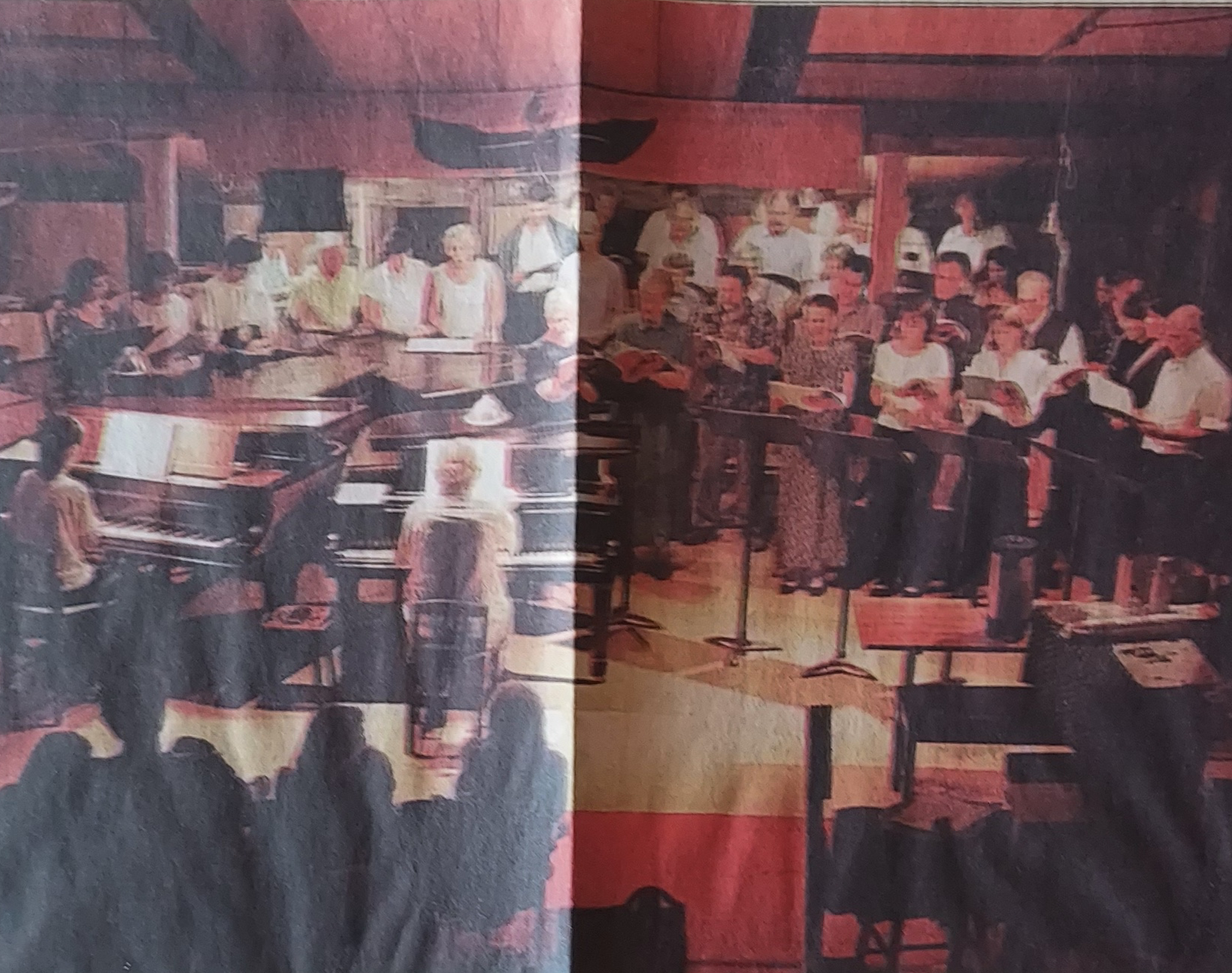

In the mid-1980's he left the zendo to establish the Surry Opera Company, a grass-roots troupe in which clam diggers, sawmill workers, architects and librarians, most of them musically illiterate, sang side by side with their Russian counterparts in performances of ''Aida,'' ''The Magic Flute,'' ''Boris Godunov'' and other operas, both in Maine and in the then-not-yet-former Soviet Union.

The Iron Curtain has been dismantled, but every summer the curtain rises on the Surry Opera -- though, like the iron one, this curtain is metaphorical. In Surry the music is made in a former hay barn. The barn stands on Mr. Nowick's farm, on a gently sloping hillside from which you can see, in summer, the tourist-clad peaks of Mount Desert Island and, in winter, the blue of Blue Hill Bay.

Simple, I thought. A story about a man who had freed himself and made others free.

Dealing with a Zen master would be tricky, of course. He would be prickly, a man of few words, and those few would be riddles. One false step, and I'd be out on my ear.

Having meditated steadily during the long drive to Maine, causing only a few minor accidents, I was braced for this. I was not braced for the person who opened the barn door, a well-knit man with wide-set, sky-blue eyes, a cloud of white hair, a genial smile and no shirt (he had expected me later), who talked unflaggingly for the next two hours.

Gusts of memory blew through the barn. They stirred dust from the barn's tokonoma, an alcove holding framed photos of Mr. Nowick as a King's Park, N.Y., farm boy; of his mother at 99; of his father, a Russian immigrant of ferocious will who built a fortune from potatoes and real estate, and had energy left over to play the piano; of his Juilliard teacher, Henriette Michelson, who brought him to Maine for musical summers and in whose Upper West Side apartment he first stumbled on a Zen poem.

Only later -- after I'd talked with some of the Russians bunking in the former cow barn -- was I shown ''the most important thing'': the cabin in which Mr. Nowick does his zazen, his ''sitting,'' amid Japanese texts and the relics of his teacher, Zuigan Goto Roshi, a great master of the rigorous, koan-centered Rinzai school. It was Goto who, inspired by a Beethoven sonata Mr. Nowick liked to play, gave him the Zen name Gessen, or Moonspring.

At that evening's pianoganza -- for the Surry series has many fringes dangling from its operas -- a herd of five pianos was arrayed in a semicircle, as if to face off wolves. (Maybe they were shielding some toy pianos in the rear.) From left to right: an oak-finished Schubert upright; a black Steinway baby grand with gingivitis, from the Long Island farm where Mr. Nowick grew up; a Knabe concert grand with the black paint stripped on the sides to reveal vibrant mahogany; a black Ibach baby grand; and a new black Yamaha upright.

Wholly unlupine, audience and players joined in a happy muddle.

''Hello, Beth,'' Mr. Nowick said to a tall, austere woman seated just to my left.

''Hello, Walter. What am I playing tonight?''

''Fourth piano in the Bach. And the Debussy, and the Japanese songs.''

''The Japanese songs? Oh, shoot.''

''Don't worry, someone will have them. You can drop a note in here and there.''

My concern that he might call on me next was unfounded, but it seemed a near-run thing. From the Mozart Variations for Four Hands, in which Mr. Nowick was joined by a lovely and gifted young pianist from the St. Petersburg Conservatory, Yuliya Yakevlenko, the concert moved through arrangements of Mozart, Bach, Debussy and three piquant Japanese folk songs -- the number of hands increasing jerkily, as in the nightmare of a scuba diver, to a sum equal to two octopuses.

Necessarily sloppy, often inspired, the concert was fun but not what I had come for. After all, these were trained pianists if not professionals. I wanted to hear the opera.

Amateur choruses abound (or used to), but opera is supposed to be hard. If it isn't, why can three tenors acquire more wealth in an evening than the Three Kings ever dreamed of?

The official story goes like this: In 1983 Mr. Nowick saw ''The Day After,'' a TV movie about the aftermath of nuclear war. Even for someone who had served in Okinawa, this was strong stuff. Shocked out of the contemplative path, Mr. Nowick cast about for a kind of activity that might help avert the threat. To warm up, he gave a series of recitals in Ellsworth, the local metropolis, to benefit the disarmament group Ground Zero. He played all 32 Beethoven sonatas, washing them down with 32 by Haydn.

But enlisting 88 keys in his project did not satisfy him; he wanted to enlist his neighbors as well. And so the opera troupe was born.

Inspired by Tamotsu Kinoshita, who had led an amateur ''Aida'' in Kyoto for which the young Mr. Nowick had played piano (the empress's sister was one of the singers), Mr. Nowick adopted the ''bum'' method of teaching:

''Can you sing?''

Heads shake.

''Can you sing this? -- Bum.''

''Bum.''

''Bum-bum-bum.''

''Bum-bum-bum.''

And before you know it, you have the first chorus of ''Aida.''

Apparently it worked, for within a year of its founding the Presumptuous Opera Company (its maiden name) was being cheered at Wolf Trap in Virginia. Mr. Nowick then had the notion of doing ''Boris Godunov'' in Russian, for Russians, and eventually with Russians on the theory that people who sing shoulder to shoulder, with one breath, can't fail to realize that they are members of one species. Tours of Russia, Soviet Georgia, Japan and France have been, by all accounts, triumphant. Most of the participants have paid their own way, but Russian visitors to Maine have been subsidized by private contributions, notably from Mr. Nowick himself.

For ''The Magic Flute'' on Friday night the barn's pianos were herded into a tight mass, with only Mr. Nowick's trusty Steinway and the big Knabe, on which Yuliya Yakevlenko would cover some of the bass and middle parts, showing their teeth. Behind and around them, on every inch of floor east of the coffee urn, were arrayed the chorus and soloists.

Mr. Nowick called the proceedings to order by saying ''good evening'' in five languages, each greeting returned obediently as if by a class of first-graders.

''We have Americans and Russians singing tonight,'' he said, ''but we don't have any Japanese.''

''I'm Japanese,'' a voice called from the back row. ''Don't leave me out.''

This was Alan Wittenberg, the most faithful of Mr. Nowick's disciples, a music therapist with an office here on the farm and one in St. Petersburg (Russia's first). He was promptly struck on the head with a choral score by Charlotte Babski, a tall, no-nonsense retired operating-room nurse with high curls who is tired of being identified as Walter's sister.

Mr. Nowick does not sit in lotus position at the piano. Nor does he hit choristers with his baton when their attention flags, although this may be only because he doesn't use a baton. He conducts from the piano with his left hand, sometimes with both hands, with gestures that flow naturally from the release. Even when there is no one to conduct, his hands float up from the keys to shape a phrase in air. ''He places his big hands very delicately,'' said Yuliya Firtich, the director of a St. Petersburg folk-song-and-dance troupe that was visiting the farm, taking part in Mr. Nowick's performances and offering some of its own. Mr. Nowick plucks at the keys as if on the strings themselves, using the sustaining pedal to give the notes full value, freeing his hands to conjure spirits.

(Did Myra Hess play that way? I can't say: one was often distracted at those concerts during the blitz. But the delicacy of sound rings a bell. Of course, I say this only because I happen to know that Dame Myra was a friend of Henriette Michelson, Mr. Nowick's teacher, and when she was in New York, she would play for Michelson and her students, and they would play for her.)

I know much about opera, but I don't know what I like. So I brought along a real critic, someone who had seen ''The Magic Flute'' rendered by the Metropolitan Opera, the New York City Opera and the Amato Opera, not to mention the Salzburg Marionettes. Jaded by the glories of world-class voices and steam-snorting dragons, how would she react to an unstaged, undressed version by yokels in a barn? With a snort of derision? A yawn?

She did yawn, once or thrice. But then, she'd had only a short nap that day, about half what she was used to in preschool. In the main she was riveted -- though less secure fastenings came to mind as she leaned over the cedar-plank balcony, a bat lured by the princely flute. (A flute, played by Irina Chernayova, did pipe up at crucial moments.) Since Mr. Nowick grew up on a farm, I had to assume that the woodwork would hold.

Though I'm sure she was impressed by the strong choral singing, the great fascination for the Critic was figuring out who was who. Not only were the singers in civvies, but they kept changing roles. The tall, stiff Tamino who had entered pursued by a dragon was relieved, for ''Dies Bildnis,'' by Sheldon Bisberg, a bus driver in a Hawaiian shirt, with a tone nasal but true. (One of Mr. Nowick's Zen students, he sang the False Dmitri on the first Russian tour.) The Critic asked me why they'd switched, then ventured, ''I think the first one doesn't know this part.''

The payoff came near the end. As Papageno -- for most of the opera a ringer named Stephen Bryant, who has been featured at the City Opera -- searched in vain for his tootsie, the Critic whispered, ''Have we seen Papagena yet?'' I shook my head. She turned out to be an elderly lady in close-cropped curls, sandals and a cobalt-and-burgundy-flowered mu mu, who had already appeared as one of the Three Ladies and briefly as Pamina (a role taken otherwise by a queenly, bulbul-throated pediatrician from St. Petersburg named Erena Egorova). She later identified herself as Kathleen Sikkema, organist and choir director at the Unitarian Church in Ellsworth.

The delicious irony -- that the 18-year-old sex-pigeon who enters the opera, in dialogue omitted here, disguised as an ancient crone should stand revealed at last as, well, an ancient (if well-preserved) crone -- was capped at the close of the ''Pa-pa-pa'' duet when the youngish, handsome baritone jubilantly kissed her hand.

A very Surry moment, I thought, and very Zen. All our faces are masks. Saint and devil, sage and fool, virgin and crone -- all drop away.

And wisdom? Wisdom is to grasp the hand of life and give it a big, wet kiss.

In the woods and barrens between Bucksport and Bar Harbor, you can't throw a blueberry without hitting someone who has sat with Mr. Nowick, sung with Mr. Nowick or both. Happily, people Down East are used to being struck by blueberries and rarely take offense. We checked into the Blue Hill Farm Inn and found that our hostess, Marcia Schatz, had been part of the first mission to Russia and Georgia in '86. She'd studied tapes of ''Boris'' while working in her garden and while commuting to her day job at the library in Ellsworth.

On a table in the main parlor I found a memoir of life in an unnamed American Zen community. The gnarled branches and sea-worn rocks on the jacket were unmistakably local. The book, it emerged, was the middle of three by a former student, now a best-selling author of fiction, in which Mr. Nowick is depicted with barely a loincloth to hide his identity. The first two books lionize him, as senior student in Kyoto and as master in Maine. The third puts him through the wringer.

Disillusionment can be a form of illusion. As any chronicler of gurus, swamis, saints and roshis knows, the shores of enlightenment are littered with beached egos, flailing violently or giving off an odor of decay. Zen masters are expected to exercise power, then are routinely accused (by Western students) of abusing it. If certain of Mr. Nowick's students see him that way, others strenuously disagree. Many have followed him into the concert barn and to points east.

Apart from ''The Day After,'' one wonders what vectors may have affected his change of course. Did he, as master, feel like a captive? (Though the dying Goto had advised him to wait 10 years before taking students, he was more or less drafted as roshi by seekers who had heard of him through the Zen grapevine.) Did he escape by returning to his first love, music? As Alan Wittenberg said: ''One thing Zen is about is freeing you to be who you are. This is who Walter is. He loves to perform. He loves the limelight. He loves to accomplish impossible things. He has the kind of energy that conquers nations.''

Which is not to say that Zen was just a means to an end. One could argue that music was a continuation of Zen by other means.

Both have to do with breathing (though, come to think of it, so does everything else). ''You can meditate by singing,'' Mr. Nowick said, ''when you take a breath and your whole soul is in that sound.'' Asked whether he goes back and forth between zazen and the piano, he said: ''Yes, but it isn't back and forth. They are one. Just as the fingers on this hand are one. Though they can be a hundred, if you play badly.''

As Schopenhauer (a Buddhist of sorts) and his disciple Nietzsche knew, music teaches not just the unity of all people, but the unity of all things. So the Surry Opera goes deeper than cultural exchange, deeper than glad-handing glasnost. Its true project is enlightenment. (Of course, the goals dovetail, for we assume that enlightened people do not drop bombs.)

Opera may seem an odd choice. It is an art of excess. (The one Zen master I know well hates opera.) But the very grandiosity of grand opera suits it admirably for teaching that if you climb out of the box your ego keeps you in, you can -- in the words of another of the Critic's favorites, ''Blue's Clues'' -- ''do anything that you want to do.'' Or at least, more things than you would have guessed.

Whatever demons may have beset Mr. Nowick in his role as master -- as the man who had transcended ego and desire -- they are perhaps shaken off, or at least placated, in the realm of music, where he becomes a different kind of teacher. Not the Sarastro who is guardian of a rigid sect, subjecting acolytes to trial by silence, hunger and pain. But something more on the order of the Three Boys, who gigglingly tell Papageno to turn around, because his heart's desire is right behind him.

Masks fall away; selves are unstable as water. But if Mr. Nowick's methods have changed, the same spring courses beneath.

Fred Ketchum, one of Mr. Nowick's first Zen students and then (with no prior musical training) one of his first choristers -- he toured Russia five times, Japan once -- tells this story about the sawmill and farm where many of Moonspring Zendo's people earned their daily bread:

''We had a full contingent of dairy animals, and we had domestic geese. We also had some Canada geese that made their home here. And Walter would help to get the young Canadas to fly.

''If you walk out of the barn and turn to the right, the road goes up. Walter would bring the Canadas together and, with his arms all wide, would make them walk up the road. He also included -- I don't know why -- some domestic geese. There was one called Whitehead: just a regular mama, her bottom touched the ground, she kind of waddled. She wasn't in any way elegant like the Canadas are.

''With his arms all wide, he would just walk them up and up, and then he would slip behind them and rush on them, going downhill. They took off and went over Morgan Bay. And they would soar over Morgan Bay and then come back to the barnyard.

''Well, he taught Whitehead to fly along with the Canadas. And I think that's what he did with the Surry Opera.''

''Is that your solution?'' the Master asks.

His hand is on the bell.

A version of this article appears in print on Sept. 2, 2001,